Pop-Culture tales of near-human, nonhuman body-sharing sentience.

A mind not yours within your flesh.

I recently finished Hunter X Hunter and Parasyte. Both evolved into surprisingly complex stories about humanity and its Others; non-human minds sharing the human world, and sometimes flesh. How mankind might relate to souls-not-ours in bodies somewhat alike, and what that unnatural mirror might speak.

I will quickly leap through some of the more prominent fictions, at least those with which I am familiar; some works of the ever-recommended Peter Watts, Parasyte by Hitoshi Iwwaki, the Chimera Ant arc of Hunter X Hunter by Yoshihiro Togashi and the Genestealer Cults of Warhammer 40k.

SPOILERS BELOW FOR ALL OF THESE,

INCLUDING THE BIG REVEAL IN 'BLINDSIGHT'

Thing-Verse Fictions

Peter Watts

Judging by how much 'Blindsight' gets recommended to me, everyone already knows about this so I won't go into too much detail. Peter Watts writes somewhat dark n edgy Science Fiction. I feel like including him here is something of a cheat as the other properties discussed are all much more ‘pop’ and Sci-Fi must be full of many examples of nonhuman intelligence.

Yet as a matter of direct experience; everyone who reads this blog asks me to read ‘Blindsight’, so I did, and Watts works chimes deeply with some of the other fictions I write about below; especially ‘Things’ and ‘Parasyte’, which could almost be parallel texts.

Blindsight

Uncommunicative Aliens show up in the Solar System, earth sends investigators. On the human side we have a resurrected Pleistocene vampire form of 'Homo' with a genius intellect, a precisely induced schizophrenic with multiple personalities, a brain-altered cyber-drone guy, and another cyborg with enhanced pattern recognition but no empathy.

The big reveal is that the aliens are intelligent but non-conscious, and see consciousness as a disease or infection they want to wipe out.

‘Blindsight’ is so concerned with human consciousness and its nature that it’s almost a jeremiad against it. In a near anti-humanist reversal of Roddenberrys civic humanism, or Dunes post-Jihad human maximisation project, in ‘Blindsight’, when humanity sends its ‘best’, it sends its least human. ‘tis a crew without normies; everyone is brain-damaged, cybernetic, a computer or literally a predator.

It is a deeply tragic text. Co-Existence is literally inconceivable. The aliens so alien that there is no person, personality, self, soul or mind to even communicate with. Simply a living entity that instinctively, intuitively, absolutely and intelligently, regards mankind and all its products as utterly inimical. The only communication being akin to playing high-stakes poker against a computer holding a loaded gun. Even the intra-human aspects are deeply in-human. Everyone betrays each other at the end.

Though, the presence of a plot-completing antimatter explosion and the sheer feral will of humanity as a collective to survive and prevail, has a lot in common with the doom of the Chimera Ants at the hands of Chairman Netoro.

The view of Mankind as a nasty species in a bad Galaxy fits in reasonably well with the 40k verse as well.

‘Things’

In 'Things' Watts imagines the intelligence of the 'Thing' from the movie of the same name, as it encounters and merges with the, to it, utterly horrifyingly alien, singular and isolated intelligences of humanity. ‘Things’ is a great story. Its short and it works as an addendum or inversion of the events of the well-known film. You can find 'Things' here https://clarkesworldmagazine.com/watts_01_10/

The being, or sentience, of ‘Things’, is familiar with a galaxy scattered with living worlds made up of unified minds. Biospheres of complexity, but like the water-world of ‘Solaris’ (which perhaps deserves attention here, but I am not made of free time), living systems which are broadly one ‘self’. In simple terms; the planet is a person. When you go to a new world, you meet and merge with a person, sharing unutterable depths of knowledge, selfhood and experience, before separating and going on your way.

Wounded and starving, when the ‘Thing’ meets humanity, it has absolutely no idea what to make of what it finds. The biosphere is mute, seemingly dead in some mysterious fashion, almost a ‘zombie world’, and physically highly aggressive; actively, blindly, mutely trying to destroy the visitor. Has this poor world gone mad? Or is the visitor simply trapped in some plague-hospital, mental treatment centre or zoo? What is going on? Why will nothing communicate and why does everything attack?

Its only slowly, and with mounting horror, that the Visitor slowly comes to understand that the pseudopods it has been trying to talk to, then fighting, avoiding and finally imitating to survive, are each, individual, separate, mutually-antagonistic minds. This world has somehow evolved wrong, creating these ‘intelligent cancers’ which prey and feed upon each other. When the visitor absorbs an exploratory limb of this world, there is a whole other person in the same flesh, emanating desires and commands from the complex knot of thinking cancer in the topmost sensory bone-case.

‘Things’ is not quite as midnight-black as ‘Blindsight’. The two entity-groups can actually communicate, and mutual destruction is not absolutely necessary or inevitable, but each side instinctively loathes and despises the other as being fundamentally wrong, monstrous and inimical.

No-one is even trying to get along.

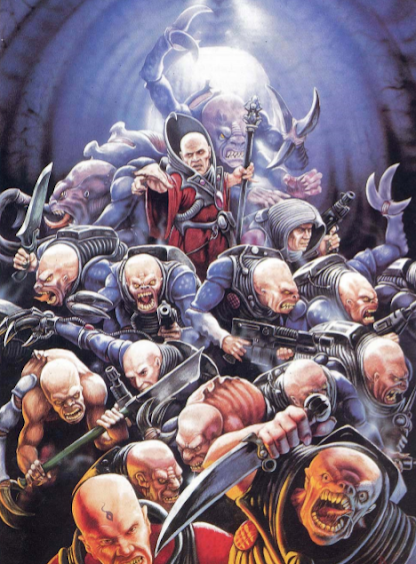

The Genestealer Cults

The Tyranids; a biological homogenising swarm obsessed with devouring every living thing, digesting it, and turning it into itself. Farming apparently is not enough; they have to strip a planet bare, pipe up the goo, turn it into swarms and on to the next.

What exactly the Tyranid Hive-Mind actually is, is a mystery of the 40k setting. Its represented a little differently each time. Like Watts ‘Scramblers’ it may not even be conscious as we understand it. It doesn’t speak. Seems to have no language. Its only relationship with any form of life is to eat it. Its only relationship with anything else is to move through or around it to get to the life it wants to eat. Its methods for doing so range from massive and brutal to unbelievably sneaky and subtle, but it could just be a problem-solving machine.

Elements or aspects or pseudopods of the Hive-Mind do seem to be allowed something like ‘personality’. It has super-General organisms which it keeps backups of, recreating them and embodying them for different wars or battles. Likewise it has super-infiltrator and super-psychic entities.

When I imagine the Hive Mind I imagine it as treating sentient self-consciousness as something like cancer, or a necessary toxin it has to generate and use to achieve its aims, but one it really doesn’t want to spread; ‘mind’ can grow, spread, infect, create copies of itself, even, like prions, perhaps instantiate flawed or destructive responses in non-mind that can lead to system failure.

The Hive-Fleets of the Tyranids also seem to be allowed a degree of ‘Personality’; distinctive tactics and preferences, complex and unique approaches to problems. Hive-Fleets can even go to ‘war’ with each other, trying to devour one another. This seems less like a war between factions but a conflict between thoughts, or philosophies, within one mind that is not a mind.

When I imagine the Hive-Mind I imagine a woman asleep in the darkness between stars. Vast. Her limbs and hairs and fingers separate and spread out into a trillion trillion pseudopods and tendrils. She is sleep-walking, or sleep-acting. Dreaming yet performing complex actions. Like someone doing the dishes or loading a gun without ‘waking up’. There is no ‘person’ there, and the dream-self fears and hates ‘personhood’.

The Cults

Genestealers are a Tyranid infiltration and subversion organism. Sent ahead of the Hive Fleets, they hang around in sneaky spaces till they encounter some kind of organised life. They then subvert and implant that life-form, turning the will of their prey to the needs of the Hive-Mind, breeding Genestealer/Target hybrids of greater and greater sophistication.

As bonkers as the Genestealer-hybrid cycle sounds, it actually makes more sense than a lot of the scientific, but semi-magical abilities of the Watts-verse or ‘Parasyte’. There is no need for biological super-beings with which every cell is an active and independent part, and where every cell is basically also a neuron, but the organism can still organise itself effectively.

Genestealers start by subverting members of the target species. At first these people don’t know they have been subverted, the incident itself is blanked from memory. To them, it feels like a spiritual or philosophical shift. They gather with likeminded people and gain a form of religion, one like, but somewhat distorted from the standard accepted doctrine. It seems like a pretty fulfilling life.

When subverted individuals breed they produce hybrids in which the genetics of the Genestealer are synthesised with that of the host species, about 50/50. These are monstrosities, but various forms of conditioning kick in and the parents adore and raise their monster-babies.

When the first generation breeds they produce somewhat more-human hybrids capable of more humanlike behaviour. When this second generation breeds they produce mostly-humanoid but still freaky offspring. When that third generation breeds they produce creatures which can pass for human and move in a sophisticated way through human society. The fifth generation includes purestrains who can re-start the cycle.

This can only really work in complex environments with big human populations, with space for the first few generations to go to ground, but enough complexity for the fourth and fifth to perform useful actions in society.

All members of a Genestealer Cult stay loyal in all circumstances. Its not clear how this is achieved. The Hive Mind, and the original Genestealer Patriarch, have a strong and subtle psychic presence. Presumably this combines with highly sophisticated genetic, chemical, behavioural and other methods to create a kind of unbreakable unity, even in highly complex organisms.

Yet. Some books take us deeper into the minds of Genestealer Cultists, and what we find there is a curious blend of delusion, compulsion and an overwriting of basic human drives that does, at times, leave room for something like brief doubt. In ‘Day of Ascension’ a young cult magus is cut off from the psychic presence of the Hive-Mind and, examining her own motivations, doubts for a moment. In ‘Cult of the Spiral Dawn’ a guardsman enchanted by a female Magus is let slip from her influence once he becomes useless, and before he dies suffers a nightmarish dark night of the soul as his certainties fall away. And there are always distaff cult associates on the side of revolution; people working and fighting alongside the membership who share similar goals, or people part of the same social network, but not fully suborned.

In making the ‘Other’ a parallel, insidious society, that runs directly alongside the main human one, the Cults bring the problem of motivation into stark contrast. The Cult is a Cult; it has a religious aim, of union with the perfect Star Gods, and a redemptive ideology. It also feels good to be a member. To be part of a giant family and to be working towards a great purpose. Cult members tend to function better than normal members of society.

What kind of twisted perversity would be needed in a human mind to actively turn against a society in which all the most fundamental drives are met and the most fundamental values and needs answered? More simply; how can we possibly think outside or against our deepest inherent values? These values are not simply ideas we choose and can swap; they form the basic axioms upon which all other thought is built, with which our moral desires are interwoven, and they are the drives which make us live, learn, suffer and grow. The very engines which impel us to action and which make up the matrix of our moral and emotional world. If something can subvert that, it is like a killer code against which Humanity has no meaningful defence.

Parasyte

Parasyte by Hitoshi Iwwaki exists in a variety of forms, from the original Manga to a live-action Netflix adaptation; ‘Parasyte: The Grey’. I am talking about the anime; ‘Parasyte: The Maxim’ which is the only version I have seen.

Our hero Shinichi Izumi is a normal Japanese Schoolboy.

One night curious spores drift down from space. One encounters our protagonist and rapidly consumes and replicates his flesh, but due to a highly unlikely series of events, (he had his own arm in some kind of cord for reasons), it only manages to infect one hand and lower arm.

The Parasyte is an adaptive and infectious distributed cellular intelligence, a lot like the 'Thing'. Every cell is apparently a trachtomrphic muscle and a neuron and it can do a bunch of things human flesh cannot. Its base instinct was first to reach, then absorb and replicate the brain and head, using these to control the body, which would remain human, yet under the control of the Parasyte. But the period of peak-adaptation for the creatures life-cycle is now over and it is stuck as the hand of a teenage boy. It draws its life from his body, from his blood supply and cannot survive without him. The creature cannot transform to adapt to a new host. If the boy dies, it dies.

Every, (or nearly every), other Parasyte that fell succeeded in its main drive and worked its way to a human brain, devouring, remaking and simulating it to control the body, and is now walking around as a simulated human being.

The Parasytes seem to be hard-coded to hunt and consume the living flesh of the species they imitate. They are very highly intelligent, capable of learning highly complex human information quickly enough that they can broadly fake being human within a day or so. (A neat aspect is that they do seem to have a natural variation in intelligence and personality, some Parasytes are highly intelligent near-artists of simulation with a deep intellectual interest in everything human. Others are pretty dumb and just about smart enough to walk about.)

Their intelligence is utterly nonhuman. Their first instinct is ‘I want to eat the brain’. After that their instinct is to hide themselves and secretly feed on the target species. (Humans). Initially, Parasytes have no sense-of-species. They are not inherently social organisms. They have no shared culture. They are not necessarily on the same ‘side’, in fact each could be considered a ‘side’ of its own. Their only collective actions are driven by pure advantage.

We never find out where the Parasytes come from, if they have a purpose or are simple a natural phenomena. We also never learn if simulating an intelligent self-aware species is normal for them. Judging by how things go, it may not be, as simulating humanity brings a towering stack of complexities.

Shinichi calls his Parasyte ‘Migi’ which I think means ‘Right’ for his right hand. Having a name is also not something Parasytes seem to inherently think about. Now the teenage protagonist and Migi are stuck together, both vulnerable to the other, both also learning from each other, in the middle of an alien predation invasion and the secret war being fought against it.

Neutral

If the ‘Scramblers’ from Blindsight are a natural disaster, the ‘Thing’ from things has a near religious disgust for humanity, and the Genestealer Cults are basically a predation/farming technique dedicated to eating humanity, ‘Migi’ and some other Parasytes, are seen surprisingly neutrally by the story. There are almost no ‘Evil’ things in Parasyte. True, some aliens are eating humans, but they need to survive and it’s their basic instinct to do so. ‘Migi’ is an alarmingly rational, even reasonable character who has no hatred or resentment for Shinichi, or humanity, but simply wants to survive, (to the extent of threatening to blind and cripple Shinichi if he goes to the authorities.

The action is not quite anti-heroic, but deeply human. At times various characters bring up the idea of acting the hero, either in the cause of humanity, or some other noble aim. The story doesn’t exactly shit on heroics, but just asks calmly; “Ok, if its really you, and you are really going to die, or your family is going to be hurt, or you are going straight to a dissection lab, how much of a hero are you really willing to be?”

Few people are evil, but most are reasonably self-interested.

The Horror of Understanding Each Other

If Watts and Genestealers breed horror from the failure to comprehend the Other, ‘Parasyte’ has a more subtle nightmare; what if you could actually see each others point of view, but couldn’t change anything?

Because Shinichi and Migi spend so much time with each other, because they learn constantly from each other and especially because they are opposed by everyone, (the government would dissect Shinichi to get to Migi and the other Parasytes see Migi as a massive security risk), they end up becoming more like each other. Confronted with the deception, self-interest and ruthlessness of the Government, and humanities utter ruthlessness to ensure its own survival, Shinichi begins to take a much more distant view of humanity. He doesn’t want people to be eaten or killed, but slowly stops defending his desires in morally absolute terms and has to admit that he takes that view purely because he is human.

Migi never changes their base ‘programming’ but they don’t need to eat people, (they draw all their sustenance from Shinichi’s blood), but they do need to protect Shinichi. Since everything they learn about humanity they get first hand from Shinichi, this is a crash course in an alien thingy adapting to the physical, social and moral needs of a teenage boy.

Migi initially has no sense of species-solidarity, being as willing to kill other Parasytes to survive as they are willing to kill Migi to remove the threat they pose. But over time, with relentless exposure to human culture, human moral arguments, human philosophy and in the middle of an inter-species war, Migi does eventually develop something like a wider species sense of self, perhaps not as intuitive or immediate as the human preference for humans, but more a top-down, perhaps intellectualised discomfort in the destruction of their own kind. Having developed this moral sense, they are intelligent enough to reverse the idea and sense how horrible it is for humans to be hunted, or to see other humans hunted. This creates a deep philosophical and moral problem for Migi.

We can imagine, the Lion being gifted intelligence enough to empathise with the Lamb*.

Other Parasytes, the more intelligent, subtle and more deeply involved in human culture, undergo parallel experiences. Only one other is in a similar situation to Migi, attached to a human after failing to eat them. The others have no ‘human half’ on which they are dependant and so are not forced to learn in the same way or at the same speed, but handfuls do seem to stop eating people, (they are strongly instincted to eat us but are not utterly obligate homovores). An intelligent female Parasyte keeps her hosts baby child as ‘an experiment’ and ends up developing quasi-maternal instincts for it. On the other side, the government discovers a nest of Parasytes working for a political candidate. After trapping them and uncovering the conspiracy, they shoot the candidate, to discover he is human. He wasn’t fooled, bribed, tricked or threatened, he knew he was working with aliens. He thought it was good that humanity finally had a predator, that the Parasytes were a gift from nature to restore balance and harmony to the world.

What starts as an alien invasion story, and is always something of a horror story, ends up developing into a kind of moral tragedy. Parasytes are exterminated, some adapt and go into hiding as Parasyte-vegans, some are so driven by instinct and hatred for humanity that they become wilderness-dwelling wendigo monsters. Ultimately Migi goes into a form of permanent philosophical hibernation, partly escaping from the moral anguish of their situation, partly seeking an answer. Shinichi is deeply lonely without his friend.

The Chimera Ant Arc

Hunter X Hunter by Yoshihiro Togashi is a Shonen magical-powers-fighting adventure Manga. Half way through its run Togashi comes up with the idea for ‘Chimera Ants’ and writes an arc for them so long that it makes up half the Anime. Hunter x Hunter is nearly ‘Chimera Ants; the Series (starring some Hunters)’.

‘Chimera Ants’ evolve through consumption, qualities, forms and memories from what they eat. The ‘Chimera Ant Arc’ begins when, somewhere, a Chimera Ant nest eats a human being and produces an Ant Queen with a humanoid form and human-level intelligence. She begins to build an ant nation by eating humans and producing generations of humanoid ants.

Hunter X Hunter has a carefully worked out magical powers system called ‘Nen based on something like ‘aura’ or ‘chi’, and which most of its main characters use. Pretty soon the Chimera Ants discover this and begin eating Nen users, producing magical Man-Ants. The Queen begins to breed an ‘Ant King’ who is intended to be the super-powerful leader for the Chimera Ants, and who is made from all the Nen users the ants can find, to create a Super Magical Man Ant.

The visuals and basic dramatic tools for the Chimera Ant Arc are cartoony and very anime (the Chimera Ants emerge from their cocoons in cool costumes), but the way it treats questions of selfhood, identity and responsibility are probably the most subtle and morally complex of all the fictions in this essay.

The Chimera Ants absorb human memories along with human shapes and abilities. They also get a bunch of semi-random animal qualities, all depending on what the Queen was eating when she gave birth to them. So any individual Chimera Ant might be a pure Ant-Minded being, just with a humanoid form and some functional intelligence, an 80% accurate recreation of a human personality, but now with an ant body and ant instincts, a wild combination of animal and human instincts, or anything in-between. Some Chimera ants remember almost nothing of any of their human parts, while some are such singular excretions of particular souls that they feel almost like reincarnations.

Many of the 'Ants' are tortured by their part-human instincts and part-human memories.

As one Chimera Ant says to another; "There's some kind of look in the eyes, I can't explain it, but I know I when I see it and I think 'yeah this one remembers their past life".

Though individually powerful, the ants lose the potency of their unity and singularity of purpose as digested qualities like price, ambition and personal desire start infiltrating their minds. The innovation of ‘Names’, (“What is a name?” asks the Chimera Ant Queen), personalities, independent drives and desires, forms a deep and inexorable conflict between these two forms of consciousness; the primal ant will to power and the human social and moral complexity.

Memory, Reincarnation and Koala

Part of the reason the initial Ant Colony is successful is because it happens inside a micro-nation called the ‘New Green Republic’, a deliberately low-tech state where people live according to a near medieval level of material technology and where everything above that level is banned. Many of the humans the ants eat initially are basically hippie peasants, which has an effect on the next ant generation.

We later discover the NGR is a front. Unbeknownst to most of its residents, the place is run by, and for, a ruthless drug cartel who use the NGR as a base to pedal drugs to the rest of the world. The initial armed conflict of the Ants is with this nest of ruthless gangsters, who they then eat, and these personalities in turn affect the nature of future Ant generations. The gangster memories synergise well in some ways with the Ants ruthlessness and will to power, but the same memories carry deep, primal loyalties and bonds, and a violent resentment that has nothing to do with Ant psychology. In their own ways, both the peaceful minds and memories of the NGR peasants and the ruthless memories of the Cartel gangsters, are toxins, poisons in the clear minds of the Ants they become. Some Ants are friends, or enemies, because of the human memories that formed them. Others are brave, craven or subtle, depending on who they absorbed. The only Ants that don’t seem to have these are the Queen, the King and the three Royal Guards, who were either very well-stirred before creation, or their ant-instincts were so powerful they obliterated any other form of selfhood.

There are many sub-stories of ants and memory, but the most strangely affecting is told through the story of this business-suited Pink Koala;

The Koala carries the memories of a Hit-Man, a ruthless amoral gangster.

"Before all this, my job was to snuff people. I'd get my orders and pull the trigger. The rest of the time I'd yell a lot. It was a job anybody could do. Even when I was reborn, it was the same thing. A stupid cycle. I wanted to let her out of it."

"Before this, I didn't believe in the soul. We're no better than fleas and flies. Life and death, that's all there is. The ego is a glitch, a side effect of a complex brain. You die and it's over. Dust to dust. Get scattered to the wind."

As a Chimera Ant, the Koala is still a seemingly ruthless killer. But the very act of dying, being consumed, and his memories regurgitated in a new form, acts as a bizarre catalyst for spiritual growth.

"Hopeless. "She was a redhead, just like you. And I gunned her down."

The differing cultural perspective is fascinating. On the Western side, the Scramblers in Blindsight were a blank-faced catastrophe, the ‘Thing’ from ‘Things’ was an enemy by nature and culture. The Genestealer Cults are a perversion of religion towards a devouring false god. Then on the Japanese side, the Parasytes are opponents, but also neutral predators, no more ‘evil’ than a Tiger, and their existence has a degree of tragedy, due to the human aspects they absorb. (Perhaps there are elements of this with the Genestealer Cults). Finally, with the Chimera Ants, they are inimical to human flourishing, at least initially, and are obligate predators, but slowly many evolve into ‘people’, ghosts or reincarnations of humanity, or aspects or shards of human nature thrown into sharp relief, each occurring in a different way.

The translation of the ‘Other’ from Absolute, to Threat, to Tragedy to Post-Humanity is fascinating to think about. If part of the subtext for any story of infiltrating nonhuman sentience is; “can inherent ‘Others’ mutually reconcile themselves”, then the wild whacky cartoony Chimera Ant arc is probably the deepest and most ‘Humanistic’ of all these fictions.

Being eaten by a magical super-ant and recombined into something new perhaps isn’t the platonic ideal of reincarnation but if you wake up with your old memories in a new body, it sure would feel like it. Dying to violence and being reborn as the incarnation of that violence, is a strange one.

Meruem and Komugi

The story goes through various, (lengthy) evolutions, with the series heroes trying to prevent the birth of the Ant King, failing, and then battling him again after he takes over a North Korea-style dictatorship.

(A fascinating aspect of battling the ants is that, if the human side lose people, the Ants have the ability to essentially ‘digest’ them, and produce Ants with combinations of their powers, memories or personalities. Meaning if you lose a friend to the Ants, you may be facing an ‘Antified’ version of them later. Depending on how much, or what kinds of memories they have, they may be an ally, a terrifying enemy, or just very confused.)

The ‘Ant King’ (his given name is ‘Meruem’, but he initially has no idea that he has a name, or any desire for one) is hyper-powerful, utterly amoral by human standards and dedicated to the Ants will-to-power and to taking over the world in a classic supervillain style.

He is also only a few days old. Though he has a well-blended cache of inherited knowledge and learns at an accelerated rate, he has no actual experience of human society or human life. After taking over pseudo North-Korea he compulsively learns everything he can, taking on and beating every human expert in every human field, and game. Until he meets the nations best Shogi player, a blind teenage girl who sustains her family by being the world champion in an obscure and complex board game. This is someone he cannot beat. No matter how hard he tries or how much he learns, he cannot win a fair game of Shogi against this girl, and she is learning from him as fast as he learns from her, meaning he may never beat her. There is something he cannot do. He slowly becomes obsessed with this game and this girl, keeping her around and playing her every day, absorbed utterly in a challenge he cannot defeat.

Because he can’t defeat this snotty blind teenager, he ends up having something like a human relationship with her. His mind becomes open to a relationship with another being that is not just a vector of imposing power or destroying a threat. He begins to analyse his own actions from an alien perspective; his compulsive murder of a child to see what would happen – that child might have grown up to be a great Shogi player. If one child might have become a great Shogi player, could there be other things that other humans could do or be that he simply doesn’t understand yet? Who actually is he? This girl has a name. His subordinate Ants have names. (They gave them to each other). Humans have names. Does he have a name? He is the King, which is all that he is, but is the King also a person like other people?

This slow ‘awakening’ or complexifying of the King worries and disturbs his closest guards. Is he starting to question the whole world-takeover thing and treating humans as livestock?

Meruem and Neotaro

The ‘Ant King’ is a being so insanely powerful that only Humanities strongest Nen-User even has a chance of fighting him so that’s who they call, organising an ant-attack to draw out the King to a location where he and Isaac Netero, the Chief of the Hunter Association, and hyperpowered shifty-Bhudda-type will fight Ant King Meruem for the future of humanity.

During this battle, the heart of the tale beats backwards. Meruem Ant-King is on a rising moral arc, gradually discovering and interrogating more of his human half, he is growing. He consistently offers to negotiate, to ‘settle this with words’.

“I have learned what power is for. To protect the weak who deserve to live. Never to oppress the defeated. I will not fight you.”

Netero, the former Granpa-figure, has been getting into fighting shape by massacring Chimera Ants. The bastion of a threatened and overpowered humanity, he has no room for negotiation or compromise. He uses knowledge of the Kings given name, taken from the dying Ant Queen, to force a conflict. In battle he exerts all his energy on destruction. He refuses all offers of compromise and ultimately, unable to win ‘fairly’, he pierces his own heart and activates the micro-Nuke he had hidden in his chest.

“Meruem, King of the Ants... You really don't have any idea, do you...? You know nothing of the bottomless malice within the human heart... I see you in hell... If there is one...”

Even this isn’t quite enough to Kill Merum, though the radiation from this dirty bomb does ultimately infiltrate his regenerating flesh, causing him to die of cancer in the arms of Komugi.

Its beyond curious that we return again, as we did with the Theseus in ‘Blindsight’ to Humanity blowing itself the fuck up with atomic weapons to kill the aliens. Humanity represented as something, perhaps individually weak, but dark and ferocious enough, and with a relentless will to live, that makes it more than equal to the threatening Other

Have We Learned Anything?

The Isolated Mind

Can one kind of intelligence encounter another without horror? All of the situations described above are horrific, though few are only that.

Is it a necessity that to truly encounter the Other within oneself, they must be opposed to your welfare

If one encounters an other, within oneself, and they are not opposed, but neutral, do they inevitably become symbiotic? Without opposition, is union of some sort inevitable?

Where are the stories about an invasive other that is not opposed, not plotting against you, or trying to subvert you, but is fine with living peacefully alongside you, as a non-human part of you? In Parasyte Shinichi’s relationship with Migi, his alien hand, is like this. They have a transactional and oppositional relationship based on mutual survival, with some threats, but over time they become familiar with each other and, though remaining in many ways fundamentally alien in outlook to each other, form some kind of friend-like bond

They even start picking up on each others morality, seemingly entirely by closeness, exposure to each other and shared threat. Migi originally has no race or species consciousness, he doesn’t care if other members of his species die, its literally fine as they are not him. Ultimately he seems to grow into or absorb some kind of group-moral-awareness, which makes his existence more and more difficult as his survival is opposed to others of his kind. Conversely, the protagonist becomes partially alienated from humanity, seeing them somewhat from the outside, not necessarily instinctively siding with humans in all situations and regarding the lives of human and alien with a degree of moral equivalence.

"These humans are definitely foolish creatures. Think as hard as those weak brains of yours can manage. Do you ever listen to the cries of mercy coming from the pigs and cows you slaughter?"

~ Meruem to Ming Jok-ik's dancers when they begged for mercy.

East vs West

Or at least, Japan vs the Anglosphere.

A lot of Japanese popular culture has a moral tone which seems lightly intuitively ‘off-kilter’ to me. At times this shows itself through a cynicism so deep, yet so petty it seems like childish abandon. But it does have another side and the stories of the ‘Parasytes’ and the Chimera Ants allow a moral neutrality, (in comparison to Watts and 40k), that actually opens access to a more complex and interesting field of moral drama.

Anthrocentric Values – Biochemical Morality

The beliefs humanity doesn’t know it has. Beliefs so core they are invisible, until contrasted with another mind within itself. Its hard for us to know what these might be until we imagine ourselves in contact with a deep-Other; something that can communicate with us, but which is so different that we have real trouble explaining ourselves.

Aye your feelings and intuitions are just biochemistry, but that is not much of an answer, (and if you are talking to a human then so is the question – equally an aspect of biochemistry).

The viewpoint prompted by many of these stories is that, through seeing humanity through the eyes of the ‘Other’, our own core values are exposed as deeply biological, programmed, and when the product of culture, are nearly as deeply rooted and immune to reason.

Beyond that, we get a feeling for the .. not just the partiality, but the near-irrelevance of any particular set of values – they feel abstract, cold, like distant laws curiously drawn, like a necessity; of course you must have values, but no more than you must have bones or a tongue.

This shows up distinctly in the Alien films where the humans have one set of messy directly intuited values, the Androids have a strong particular set of directly-coded values, sometimes with secret values hidden from others, and the Xenomorphs have their own purely instinctive survival drive

But, adrift in the blackness of space, all of these ultimately seem much of a muchness, one necessarily no better than the other.

By what right do we live?

What is the vision of humanity that emerges from the Thing-verse

Lonely. Horrifically dangerous. Callous and self-absorbed, with not much of a moral claim on this world, for it was taken and maintained by force.

Without a moral argument for its own existence.

One shadow impulse behind all these fictions might be a version of humanity that is trying to shape a moral argument for its own existence that might work for a non-human mind. Job arguing before God, but now arguing before the imagined Other.

Can you explain yourself to a Chimera Ant?

..........

* Only on reading this much much later do I realise that this is us. We are the Lions cursed with empathy for the Lamb and we are the homogenising swarm that consumes all, only discovering too late, the inherent value of what we destroy.

¯\(°_o)/¯

¯\(°_o)/¯

Patrick, you are here creating an inchoate argument for the plot arc of Star Trek: TNG, as evinced by a careful rewatching of the dual episodes, Encounter at Far Point and All Good Things.

ReplyDeleteI noticed before (in Anime/Manga) that in Japan it seems to be a legitimate question whether defending your life/that of your species is morally justified. I always felt that there are things you do not need rational arguments for. Don't want to die? Got it. Don't want your children eaten? Do something about it, if you can. I guess I'm not ready for the kind of pacifism that is like "before I strike you, I'll just let you kill me and everyone I love instead".

ReplyDeleteI don't think, any living thing needs a moral claim to life. If it had, even vegans would be murderers.

Without wishing to open a can of worms or crudely oversimplify, it is perhaps worth drawing attention to the fact that Japan is amongst many other things a Buddhist society, and that this has doubtless permeated its understanding of ethics.

DeleteBeing German I've always assumed it's more about the trauma of having been the bad guys in World War II and never fully coming to terms with that. Like questioning even the most firmly held belief that one is in the right because the fanatical belief in conquering and stepping on everything had turned out very badly.

DeleteOne could make the argument that humans are less deserving of their dominion than carpenter ants are

ReplyDeleteAs a child, I read the Animorphs book series, my introduction to science fiction/fantasy and a huge influence on my reading and writing in general. That series features an intelligent parasite race (the slug-like Yeerks) who compete on the galactic stage and enjoy such sensual wonders as vision only by hijacking the bodies of other beings. Over the course of the books, the question of their parasitic nature, how inherent it is, whether there are other solutions, and what it means to live in another being's body (against their will) is explored from a number of angles. Particularly interesting is that while Yeerks take other beings' bodies as a matter of course, they seem to have a taboo against taking someone else's host body after the mandatory feeding breaks -- and this, implicitly, is what causes the rise of the Yeerk Peace Movement. After all, taking bodies is what they *do*, but if they can view a body as belonging to another Yeerk -- and so off-limits -- some of them start making the conceptual leap to the host's body also being off-limits; they have started to "Yeerkise" these aliens. Maybe the aliens own their bodies just as another Yeerk owns its host? Does the host of that other Yeerk have first claim to its body, making its enslavement wrong? There's even a progression in terms of the species they encounter. Their first host species, the one they evolved with, is barely sapient and arguably it's a true symbiosis. The two they take next upon escaping their homeworld are easy to dismiss; the first is afflicted with bestial urges that they try to control in part by being voluntary hosts (so again, moral qualms are easily brushed aside), and the second has innately low, childlike intelligence, meaning the highly intelligent Yeerks can justify it to themselves that these are lesser beings (even though the resistance of the childlike race to Yeerk oppression is a key ongoing subplot). It's when Yeerks start infesting humans and other beings with intelligence on par with Yeerks that it really starts becoming an issue for *them* as well as their victims.

ReplyDeleteThere's also a very interesting question of how much of their host-taking *is* something they need to do to experience a worthwhile life, and how much is just the warlord culture of their leadership. We get a few strong hints that many Yeerks actually find being in host bodies disorientating or overwhelming. Tellingly, when one sympathetic Yeerk is given the option to shapeshift permanently into another form, the form she chooses isn't human or anything like it, but a whale -- like a Yeerk, it's aquatic, relies on sound more than other senses, and even has a similar shape, while losing the disadvantages of small size, vulnerability, and limited range.

Another clever point of the books is that, since shapeshifting permanently is a thing, a potential solution to the whole problem is *right there* all along -- but it's never anywhere near that simple, since all manner of biological and cultural imperatives are in play, there's great distrust between various species and factions (the ones who have the shapeshift technology are the enemy of the Yeerks), and attitudes don't change overnight.

If you're interested in seeing how these ideas are offered to young readers, I'd recommend giving some of those books a glance.

Damn who knew Animorphs went so deep..

DeleteIt really does. When you hear the synopsis -- "it's about children who turn into animals to fight an alien invasion" -- it sounds ridiculous, but it's so much more than it sounds. Revisiting it as an adult reaffirms my childhood fondness for it -- especially now I can better articulate some of those depths.

DeleteAnimorphs is great and I'd say the "deep" stuff definitely outweighs the silly stuff, even if there's a lot of both.

ReplyDeleteUnrelated to the science-fiction themes, the constantly shifting POV between books really helped flesh out all the characters.

"just read Animporphs bro" is going to end up the new "have you read *Blindsight*?" of False Machine

Delete