Curiously, just before reading this I had finished a Clark Ashton Smith collection into which the enormous and specific work and attention paid to every aspect of a pure luxury good, as well as the almost magical-alchemical assembly of these wonderous, varied and specific materials - the fur of a young kitten, Lapuz Lazuli ground with rough salt and separated by grain, soft repetitive polishing with crystal or malachite, would seem to slot almost perfectly.

While transformed-orientalism western idea of Luxurious Otherness has a pedigree which seems to flow all the way from 'Othello' to Jabbas Palace, the particulars of the creation and social milieu seem to cry out for some boutique D&D adventure - the Emperor calls for a painting and his artist, the 'Wonder of the Age', needs *this* specific kind of malachite, grains of gold and Lapis Lazuli and the tail fur of this specific kind of kitten, and you only have 50 days to finish the painting, and the artist has enemies who wish to sabotage him, and the Emperor might be about to be assassinated.. "Vorsprung durch Luxus"..

"The Technique of Mughal Miniature Painting

Miniature painters sat on the ground while working with one leg flexed to support a drawing board. (Plate 19). Their technique was deceptively simple: opaque watercolour on paper or occasionally on cotton cloth. Artists learned the trade secrets of their ateliers as apprentices, often from fathers or uncles, as this craft was frequently a family occupation. As children, they were taught how to make balanced, finger-fitting paintbrushes of bird quills set with fine hairs plucked from kittens or baby squirrels. They also learned how to grind mineral pigments, such as malachite (green) and lapis lazuli (blue), in a mortar; how to sort them grain by grain according to purity and brilliance; and how to prepare the aqueous binding medium of gum arabic or glue. Other pigments were made from earths, insect and animal matters, and metals.

(Plate 19)

To make metallic pigments, gold, silver and copper were pounded into foil between sheets of leather, after which the foil was ground with rough salt in a mortar. The salt was then washed out with water, leaving behind the pure metal powder. For a cool yellow cold, silver was mixed with it; for a warmer hue, copper was added. Because such pigments as copper oxide were corrosive, the paper was protected from them by a special coating. Some artists, such as Basawan (Plates 6, 8, 12, 13) were particularly admired for their manipulation of gold which they pricked with a stylus to make it glitter - burnished or modelled by tinted washes.

Although artists did not make paper, they were connoisseurs of its qualities. Composed of cloth fibres, it varied greatly in thickness, smoothness and fineness. Akbar' painters of the late sixteenth century preferred highly polished, hard and creamy papers, while Shah Jahan's artists employed thin, extremely luxurious sorts, possibly made from silk fibres.

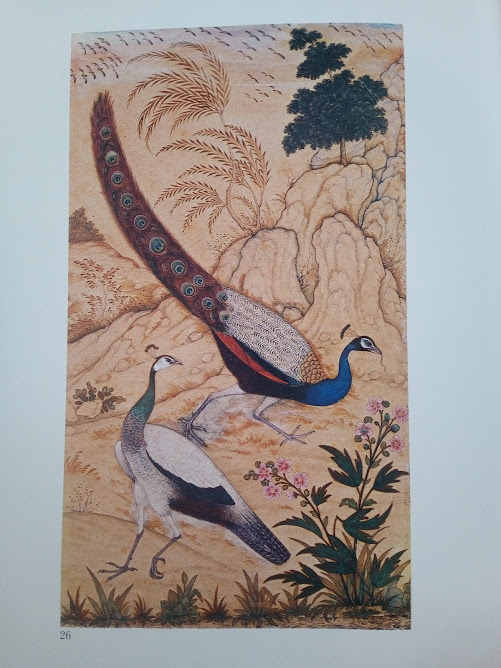

A complex, very costly series of steps involving many people was required to make a Mughal painting. Pictorial ideas usually began with the patron, who summoned the appropriate artist (or artists) to carry them out. Several of the most renowned Mughal aritsts were specialists, such as Govardhan, who was noted for portraits of saints, musicians, and holy men (Plate 24), or Mansur, famed for birds and animals (Plates 26-27).

(Plate 26)

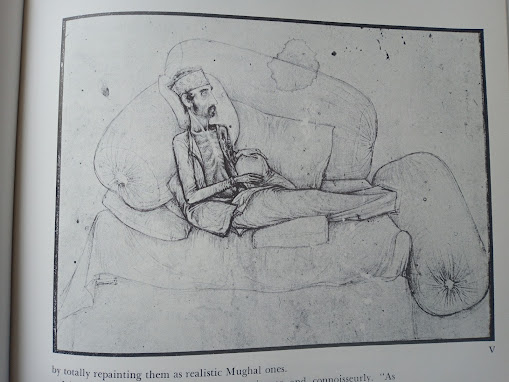

After the painter and patron had conferred, sketches, such as Figure V, were prepared. In this instance, the artist drew from life, which lent his sketch disturbing immediacy. Like others of the sort, it was intended not for the patron but for the workshop, as a model from which to paint, and it did not have to be formal and tidy. Mistakes were scumbled over in white pigment and redrawn.

(Figure V)

Later, in the artists studio, the drawing would either be copied or pounced (traced) onto the thicker paper or cardboard of the finished work (Figure V, Plate 23).

(Plate 23)

Tracing was done with a piece of transparent gazelle skin, placed on top of the drawing, the contours of which were then pricked. It was then placed on fresh paper, and black pigment was forced through the pinholes, leaving soft, dark outlines to be reinforced by brush drawing. Sometimes the original drawing included notations of colours, in words or washes of pigment.

Unfinished paintings reveal the progress from bare paper to thin outlining in black or reddish brown ink and to the many stages of colouring, which were built up layer by layer to enamel-like thickness. Usually, gold highlights were the last step before burnishing. Burnishing was done by laying the miniature upside down on a hard smooth surface and gently but firmly stroking it with polished agate or crystal, a process comparable to varnishing an oil painting, which provided protective hardening and gave an overall unity of texture.

The length of time it took to accomplish all this varied according to the painting and period when it was done. Robert Skelton and Ellen Smart discovered a small marginal inscription on an illustration to the Babur-Nameh stating that Ram Das worked on it for fifty days (see Figure II). Other paintings published here must have taken considerably longer. After the artist had finished his picture and shown it to the patron, who had probably overseen its progress step by step, it was turned over to other specialists to be trimmed, mounted on splendidly illuminated borders, and bound into a book or album, according to imperial wishes. Occasionally, pictures were mounted on walls (Plate 17).

(Plate 17)

The social position of artists varied greatly. Akbar himself learned to paint as a child; and some of the artists were aristocratic courtiers who also served in diplomatic or other governmental capacities. Most court painters, however, were revered but humble craftsmen, whose talents had earned them privileged positions near the throne. A few, such as Jahangir's favourite artist, Abu'l Hasan, who was honoured with the title "Wonder of the Age," grew up in the royal household.

Paradoxically, the lot of artists was often more secure, and probably happier, than that of princes. Arists painted on and on, from one reign to the next, while royalty rose to dizzy pinnacles of wealth and power, too often only to be imprisoned or murdered. Since all but a few Mughal rulers were keenly interested in painting, artists were generously rewarded. Salaries must have been ample, and when a patron was especially pleased, presents were lavish. Bichir painted himself in the foreground of a picture (Plate 22) holding a miniature of an elephant and a horse, gifts no doubt from Jahangir."

(Plate 22)

("Prithee allow me in thine painting sirrah".

Closeup of Bichir getting photobombed by some European dude..)

From "Imperial Mughal Painting" by Stuart Cary Welch

No comments:

Post a Comment